shaku

tea

It is called the tea ceremony, but tea is just a vessel for hospitality. In a bowl, I taste three things: the water, tea and the host's heart. But try drinking three bowls of tea on empty stomach: Tea is not always the best answer. Thus I strive to bring the same care the tea ceremony fosters to everything I serve, be it tea, whisky or a glass of water.

In saying that, in Japanese tea training, the taste of the tea is only an afterthought. However, the taste is a powerful channel of communication. So, if it's tea I'm serving, the tea better be freaking delicios.

Cheap matcha, especially, can be bitter and harsh; and there are vast flavour differences between teas. Not to consider them and find the most suitable flavour for the occasion is a shortcoming of the host. At the same time, I feel that higher quality teas can lack the bitterness that contrasts the wagashi sweetness.

My school uses the teas of Koyamaen, and while I'm not shying away from others, I like most their wako, which I usually use for its full, but not cloying umami taste. See my tasting notes of other teas.

-

0 CHF

-

0 CHF

-

250 CHF

-

2500 CHF

communication

The Japanese tea ceremony doesn't start when the guest enters the room, but when the host sends an invitation on paper (after the the date and all have already been settled upon).

This is not just a mere formality, but an essential part of the congregation: It sets the expectation, which in turn acts as a basis for the gathering. The guest knows what they can expect, and thus can gauge the level of formality (and appropriate reimbursement). The host knows about the guests' expectation, and thus can play with it.

There is the story of Hideyoshi, who wanted to see Rikyū's morning glories in the tea garden; but when he arrived, they all had been cut. Instead, when he entered the room, he found a single morning glory in the alcove. Such a surprise only was possible in the light of his expectation.

This is not contrained to the tea ceremony, though, but is relevant in today's gastronomy as well. Asking a guest what brings you here? doesn't need to be an empty formality, but helps to establish what expectations they hold.

-

0 CHF

-

500 CHF

sweets

Just before you drink tea, you'll always be served a sweet. Against the backdrop of sweetness, the bitterness of the tea is all the more pleasant. It is the bitterness, not the sweetness, that is thus accentuated. Tea is melancholy, beauty seen through the veil of transience, or more plainly, sweetness in the light of bitterness.

Traditionally, the sweets are made of sugared bean paste, which lends itself to be shaped into flowers or other seasonal motifs. More importantly, however, is the fact that it doesn't leave an oily residue on your hands or tongue that could sully your clothes or mask the taste of the tea. Because of that, translating wagashi culturally for Western palates is not an easy task, since most of our desserts contain fats in the forms of milk, chocolate or nuts.

-

500 CHF

-

0 CHF

-

500 CHF

cooking

The meal that precedes the serving of the tea has become an art in itself, but I have little talent for cooking.

For my practise, I thus stick to Jōō's principle of 「一汁三菜」, which means one soup, three sides (something vinegared, something in a shallow dish and something broiled), and remain true to the tea meal's roots in temple cuisine, which is vegetarian.

-

250 CHF

-

250 CHF

-

500 CHF

architecture

utensils

comportment

clothes

incense

flowers

calligraphy

mindfulness

What is this about?

I am a bartender who turned to the Japanese and Chinese tea rituals to build a theory of hospitality. How to help the guest – be it in the tea house, in the bar or in our everyday life – attain a state of mind complete ease, where he or she does not need to think about his or her adequacy or what to do next, but instead can enjoy a moment in peace?

humility and transience

humility in my comportment and as an aesthetic ideal. As a host, I try not to strive not to impress the guest. This is difficult, because at the same time I want to bring out the best tea, show the utmost consideration and use the finest silverware, metaphorically speaking. Yet all these should only serve to make the guest feel comfortable, not to show off my refinement, lest the guest feels inappropriate. So, for everything I do and for every thing I use, I ask: does it help the guest to feel at ease, or is it just to impress him? Am I using it for the guest's sake or my own?

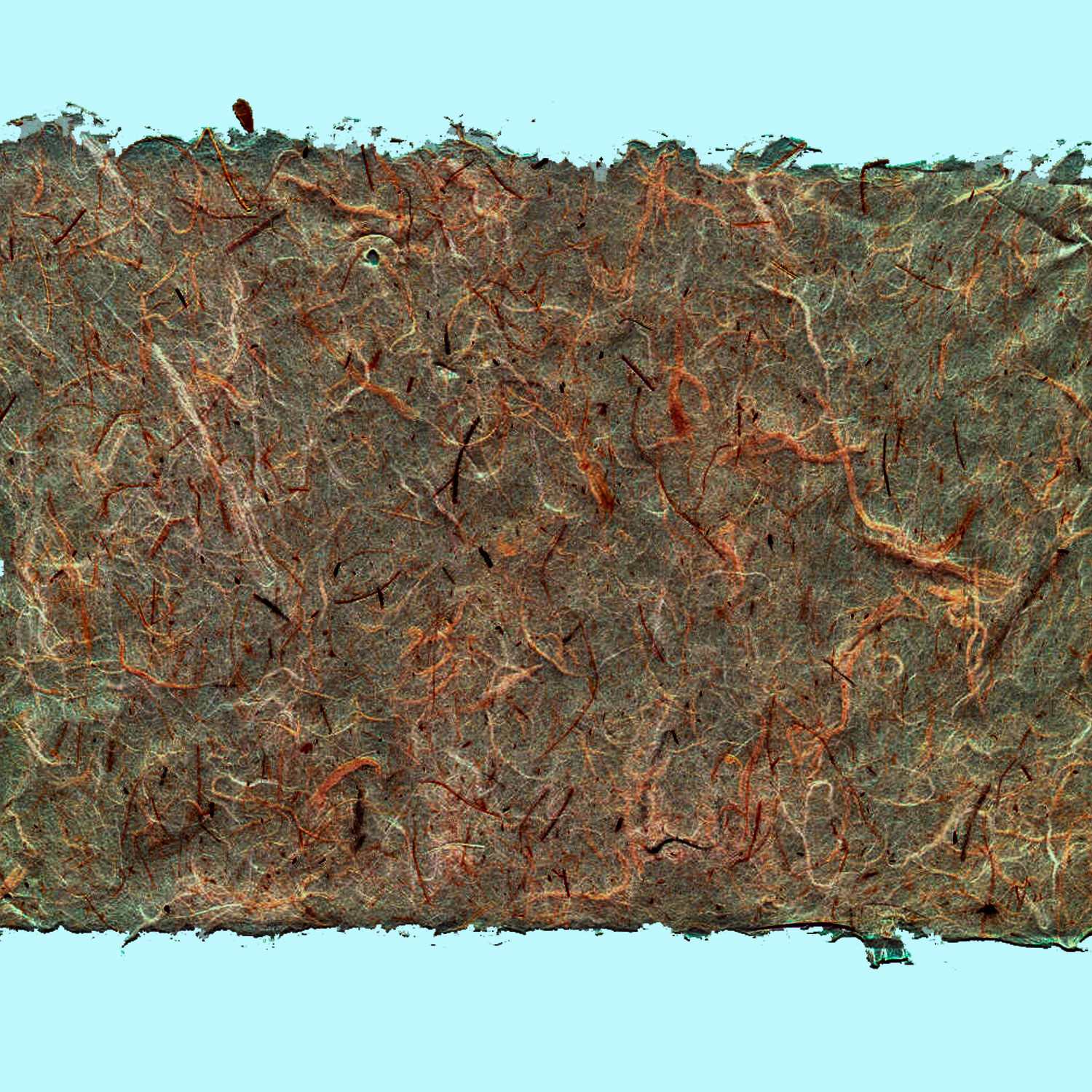

Likewise, the tools we use and the architecture that surrounds the encounter should show restraint in their elegance, so that they underline the hospitality and do not distract from it with their beauty. If they draw too much attention, the guest's mind cannot come to rest. Instead, if the guest seeks to be entertained, only then should the refinement become apparent. While many Japanese arts express such an ideal, it is not confined to Japanese culture, and I am trying to find counterparts in European designs.

transience as a guiding motif. Realising that every instant – a bowl of tea, a cocktail or a walk in the sun – is unique, and will never happen again in precisely the same way gives infinite value to it: Rare things are precious, so unique things are invaluable. This realisation is a reminder of the joy of being alive right now, and gives the guest a chance to focus completely on the here and now, temporarily sheltering him from the ghosts of yesterday and the woes of tomorrow. Simultaneously, it serves as a memento mori, and allows lightness of being that our mortality affords us put matters in a good perspective.

However, all of us often fail to see things this way, and the host can help the guest to remember this; thus increasing the guest's enjoyment. In the decoration and matters of taste, the seasons and tasteful signs of wear and use are principal. Again, while many Japanese arts embody these principles, vanitas motifs are not uncommon in European culture, at all.

Check out my  to see what I'm up to or send me an

to see what I'm up to or send me an  for inquiries.

for inquiries.